Writings - Cuba Crossing

Cruise to Cuba combines physical, political dangers

Thursday, May 6, 1993

It seems like we're aboard the S.S. Minnow at times, if not the Edmund Fitzgerald.

We cast off from Key West's Oceanside Marina two hours before dawn on April 18, our destination Cuba. But a few hours into the voyage, I begin to wonder whether we'll arrive at all.

Thirty-two years earlier to the day, a U.S.-backed Cuban invasion force was fighting a losing battle against Fidel Castro's soldiers at the Bay of Pigs, following a predawn landing on April 17, 1961.

Our mission is a more peaceful one, to reconnoiter the island as sightseers aboard the 42-foot Newfie Bullet, and report our findings in various publications upon our return. Publishing stories is one way around the 32-year-old U.S. trade embargo that forbids United States citizens other than journalists, researchers or politicians on assignment from spending any money in Cuba.

The motorboat's owner, Steward Oldford, Sr. of Northville Lumber, along with Northville restaurateur John Genitti and seven others, had originally planned to make the crossing with a flotilla bringing medical supplies and humanitarian relief to the beleaguered island nation. But when the flotilla's departure date was pushed back a week at the request of Cuban officials, we decide to sail alone, a sort of unofficial advance party for the fleet.

Our mission seems ill-fated from the start. The crew had failed to seal a slow leak in the 15-year-old ship's inflatable dinghy the night before our departure, and a depth finder on the flybridge broke down. One hour out of the harbor, as the lights of the Key West skyline slowly sink into the dark horizon, an electrical fire breaks out on the bridge. Quick action with a fire extinguisher by passenger Harry Brown, and a few repairs by captain Skip Lembright, and we're on our way again.

But it isn't long before a more serious problem develops. As we make our way across the 90 miles of open ocean in the Florida Straits, the port engine sputters and dies. It starts back up, reluctantly, and continues to run erratically as we keep heading south toward our destination at Marina Hemingway just outside the capital city of Havana.

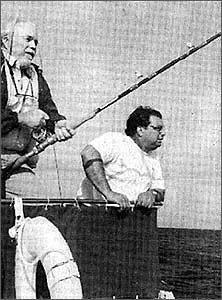

As the skyline begins to brighten off our port side, so do our spirits and our luck. The skipper sets two fishing lines and leaves the rods sitting on the flybridge, waiting for a strike, and by late morning Oldford has reeled in a two-foot mahi mahi that struck the starboard line and set the reel clattering as it pulled out the line. First mate Kellee Tartanis quickly turns it into a spicy fish stew which she serves with hunks of thick, buttered Bahamian bread left over from the ship's last port of call.

This culinary feat is made all the more impressive by rough seas encountered throughout the crossing. We have a following sea, which means the four- to six-foot swells are coming at us from behind. The Newfie Bullet, a seaworthy boat but slow, rolls backward over the swells as they head south faster than us, raising the stern first as the boat surfs briefly down the front of the wave, and then lifting the bow as the mounds of water race ahead. The boat seems to pause as it slides down the back side of each wave, turning the 14-hour journey into a series of stops and starts.

This constant rocking takes its toll on at least one passenger, who spends most of the crossing leaning over the varnished rail. Skip yells down from the flybridge that barking at the fishes will not make them bite, but the joke goes unacknowledged.

The sun is setting off our starboard bow by the time we make landfall in Cuba, spotting the Havana skyline while still several miles offshore. It looks like any mid-sized seaside city, with dozens of high-rises and a thin pall of smog.

As Genitti pilots the boat through the narrow channel leading to Marina Hemingway, an Interior Ministry official in a pea green uniform and high black boots, wearing a holstered pistol on his waist, waves us to the customs dock. Tension is high as several uniformed men appear to grab our lines, since we don't know what kind of reception to expect.

The boat is eventually boarded by a half-dozen officials and our passports are collected and returned three times, but the officials allow us to purchase Cuban beers from a passerby and one customs agent even runs across the street to fetch us a chicken sandwich.

By midnight, the first round of inspections is over and we're allowed to pilot the boat around the channel to our dock at the marina. As soon as we tie up, we're greeted by a young man bearing a tray of rum and cokes who says in halting English, "Welcome to Cuba." The drinks are made with Havana Rum, and the bartender has not skimped on the alcohol.

In the morning, which comes quickly, more officials board our vessel. A food inspector sniffs the lunch meats in our refrigerator, while an agricultural inspector checks our fruits and vegetables, pocketing one potato for "testing." Several customs officials return with a drug-sniffing German Shepard named Elf, and pause for pictures after Elf makes his rounds. I had been told in a U.S. state department communiqué that you cannot take pictures of uniformed Cuban officials, so their willingness to pose is a surprise.

Like all the officials we've met so far, the latest round are unfailingly polite.

Still, we are watched for several hours by three men parked nearby in a Soviet-made sedan bristling with black antennas, bearing what appears to be a military license plate. A thin man wearing a backpack remains standing by a lamppost when the sedan pulls away, staring casually in our direction.

We rent a tourist van for several days, which turns out to be one of the nicer vehicles on the island, and a cheerful Cuban man named Diosvil Diaz is hired as our driver. Our first destination is the mountainous and scenic Pinar Del Rio region on the island's west side, more than 100 miles from Havana.

On the highways heading out of the city, we pass Cubans gathered at every on ramp to hitch rides into or out of town. They hop on the backs of lorries by the dozen or, if lucky, are picked up by flatbed trucks with crude metal boxes bolted to their tops and a single open hole cut in the rear of the box for an exit. This makeshift public transit system has replaced the buses that have broken down for lack of spare parts.

Motorized vehicles are a rare sight in general, and the right lane of nearly every road including the highways has been given over to bicyclists, pedestrians, horsemen and ox-drawn carts. Diosvil is constantly tapping his horn to warn pedestrians who stray into the passing lane, and clear us a path. We come upon a half-dozen sugarcane workers and they wave their machetes at us as we pass, apparently angry that we would not stop.

Our van passes fields of sugarcane, tobacco, and other crops that are farmed as often by oxen as by tractors. The poverty is enlivened by frequent billboards advertising the revolution, and bearing portraits of revolutionary heroes including Ernesto "Che" Guevara and slogans like "Victory" and "Socialism or Death."

The ads seem directed at the Cuban people themselves, though it's questionable whether the natives are buying the message or simply doing what they can to survive.

Over the next week, despite his near complete lack of English, Diosvil becomes a good friend and trusted guide. He drives us around the island, from the Pinar Del Rio region to Varadero, the exclusive tourist resort 90 miles east of Havana that boasts recreational facilities cleaner and better-maintained than anything available to the Cuban people themselves.

The government maintains this control over its citizens by making it illegal for them to carry or use foreign currency, particularly the U.S. dollars that every tourist spot accepts instead of the local peso. When I ask Diosvil what he thinks of the arrangement, he shrugs and says "It's difficult, OK?" and turns away. There's an edge to his voice I have not heard before, and I do not ask him to elaborate.

On Wednesday, we take the Newfie Bullet out for a snorkeling expedition and anchor off a rocky beach that looks promising. The skipper, first mate and Genitti are in the water a few dozen feet offshore when I look up to see two men in khaki uniforms running down the beach at us with rifles at the ready position.

Harry has seen them too, and he yells to Skip, "The military's coming and they've got guns!"

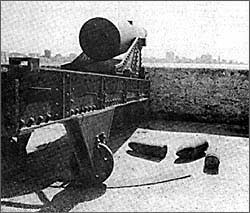

The snorkelers return to the boat quickly and the two soldiers take up positions with a third armed man about 50 yards from the shore in the shade of some palms along the beach. It appears they just want to keep an eye on us. We study the shoreline a little closer and realize we've anchored off a military installation, with pillboxes on the beach and barracks back through the trees. Over the halfhearted protestations of some passengers, Skip decides to leave.

"We've dealt with the customs guys, the interior guy and the agricultural officials, but the military is a whole different thing," Skip says. "I don't know enough Spanish to talk my way out of this one."

Adds Harry, "When you see three guys running down a beach at you with Russian AK-47s, it's time to leave."

In the following days we make several trips into Havana, the diseased but still-beating heart of this communist nation of 10 million people.

The city seems on the verge of collapse, though its residents don't appear to notice. The elegant Spanish-style buildings, those that are still standing, have gone years without paint but their faded pastel colors, pillars and wrought-iron balconies are still attractive.

The few remaining cars, big American models from the '50s or Communist-era sedans that belch smoke, are often seen broken down in the middle of the road or being pushed to the side by a crowd.

The once-scenic Malecon, a wide monument-studded boulevard that runs between the city and the sea, is now lined each evening with 17-year-old prostitutes. The working girls also crowd the streets leading to Marina Hemingway. They shout out as we pass in our well-marked tourist van, posing in their too-tight dresses.

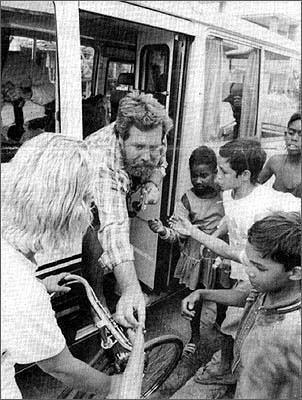

Go to any square as a tourist and you will soon be approached by dozens of children asking for candy and young men offering everything from cigars to whores. But despite the constant offers, the people seem too proud to stoop to outright harassment or theft, and even the prostitutes are good-natured when you turn them down.

By the time the first yachts of a scaled-back relief flotilla have arrived April 25, we've had our share of adventure. Cuban politicians and Red Cross officials vie for sound bites as the boaters squirm under the relentless media questioning. The fleet's presence, together with the hordes of other journalists that have descended upon the marina, seem almost an insult after the week of exploration we've done. After all, the marina has been our one haven in the midst of the country's distress.

We leave at 2 a.m. the next day, as an Afro-Cuban band plays in the tiki hut at the end of our dock. The obligatory customs check is a mere formality, as the agent quickly walks through the boat checking only the most obvious places for Cuban stowaways.

Skip has since repaired the port engine so the return voyage is much less eventful than the original crossing despite occasional eight- to nine-foot rollers. What took us 14 hours the first time now takes 10, with the engines running smoothly and the Gulf Stream current helping us along.

As we approach the shallows off Key West, and the ocean turns abruptly from a deep turquoise to an emerald green, the VHF radio blares a message from a freighter captain off the keys who has come upon a raft carrying four Cuban citizens. The local Coast Guard station operator responds that he'll pick them up, though he's uncertain what to do with them once he has.

The trip we have just completed in 10 hours must have taken them several days of drifting under the hot tropical sun, and our own journey seems suddenly like a lark.